Fang wood figures are perhaps the most fascinating and recognizable style in classic African art. A relatively large number of works were collected around the peak of the tradition, which was in full bloom when Europeans in the middle of the nineteenth century first made contact with the people then often referred to as “Pahouin”. Both missionaries and explorers recognized something special about the figures and collected them as curios, and while artistic output was never of a great scale a relatively large number of the figures were spared from external and indigenous purges of traditional religious art and ended up in Western collections and museums.

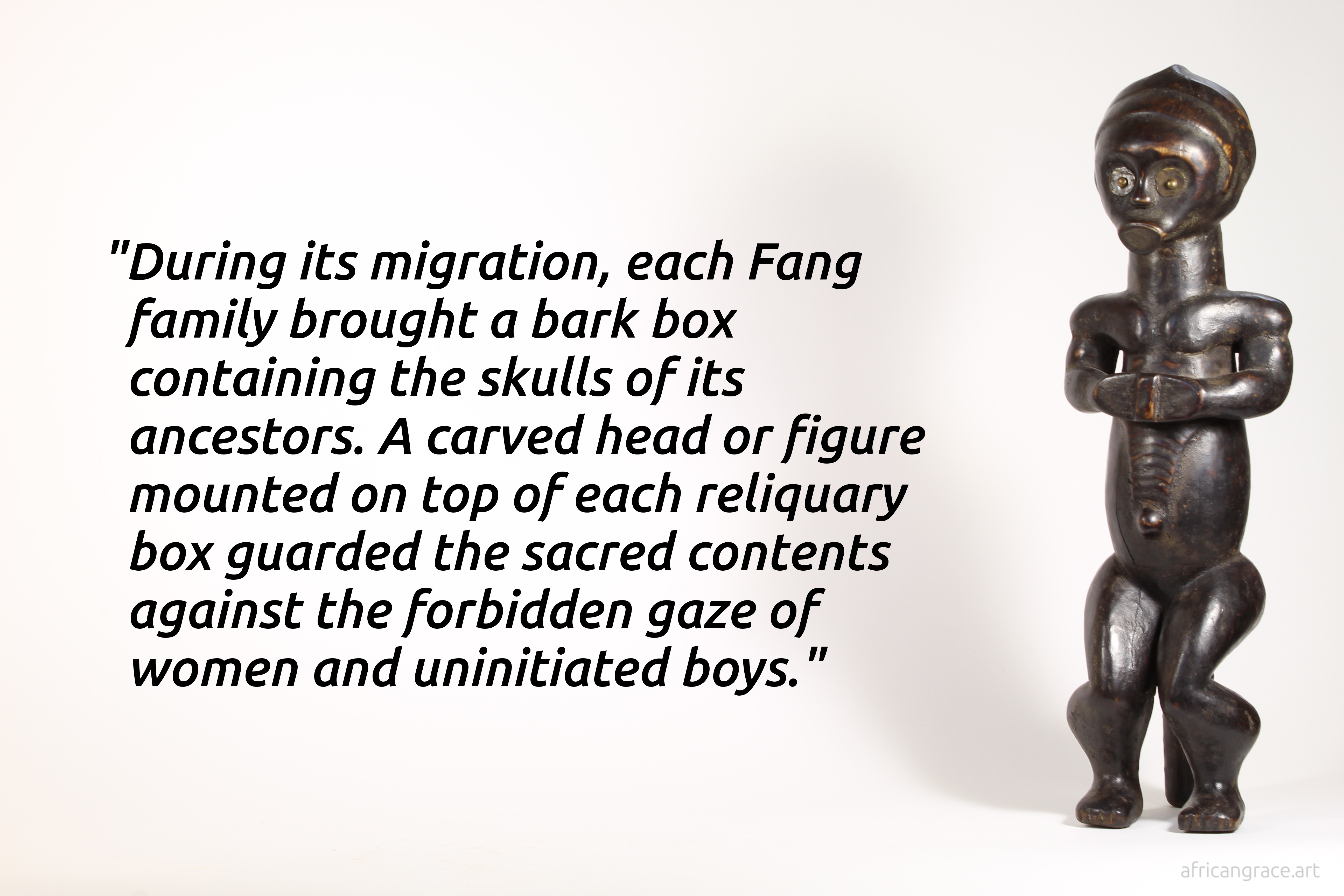

The Fang had a somewhat mythical reputation among other tribes and especially early European visitors to Africa due to their status in the forests of Gabon as relative outsiders; the Fang, themselves displaced from their lands of origin by another group, began a migration from the northeast toward the west coast around the end of the eighteenth century. As the Fang migrated they brought with them their religion and religious art, and as they assimilated and became assimilated with the existent cultures of Gabon the different paths of migration created a number of Fang sub-styles by the time Europeans arrived in the second half of the nineteenth century.

As a Bantu people the Fang practiced the dominant Bantu religion of ancestor worship, Byeri. Practice of Byeri is especially centered on the relics of ancestors; through the relics the living can interact with and make use of the power of the spirits of the dead. Any part of an ancestor could be a relic, however the items with the highest concentration of power were the skull bones. For the Fang, as most traditional African cultures, the head was the residing place of the spirit.

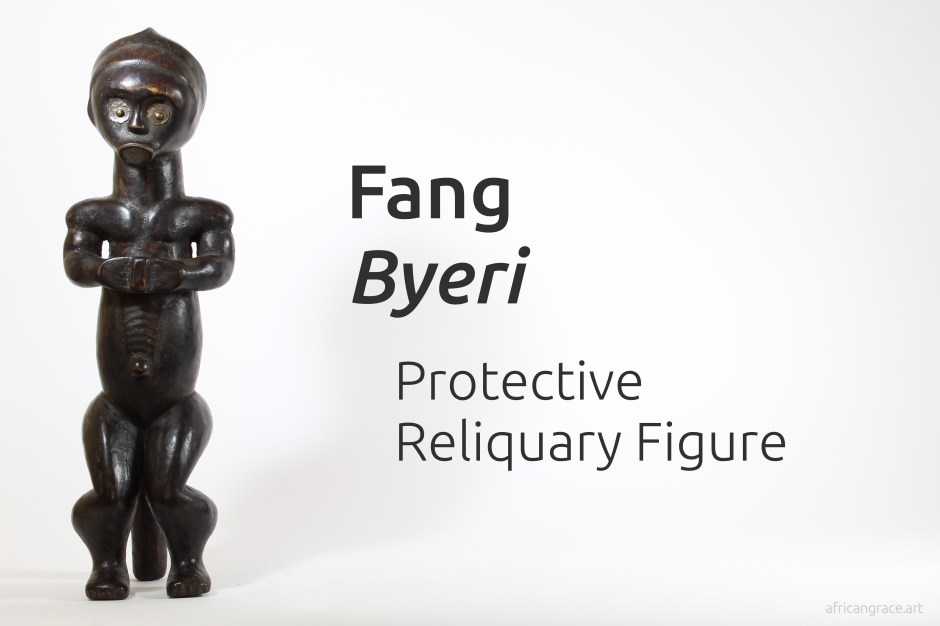

As a patrilineal society Fang family descent was through the father, so the relics of a family’s dominant males were most powerful. When the head of a family died he would be buried close to the heir, either in or very near his house. This would prevent others from taking the power of the lineage, no doubt a spiritually devastating event for a family. Several months after burial the relics were exhumed and cleaned and oiled and added to the family’s collection of past generations of ancestor skulls. They were used in ritual and consulted for guidance in times of stress, but when not in use were usually kept in round reliquary boxes made of bark. Atop the lid of the box would sit or stand a wood figure, or less often just a wood head, called “biyema byeri,”. The purpose of the byeri figure was to ward off human intruders and malicious spirits from the relics. The figure itself had no intrinsic power; its power came from its association with the relics in the reliquary box. By channeling and projecting the power of the relics within the box the byeri becomes a spiritual tool used to bridge the gap between the living and the dead.

Many byeri were both anointed with and preserved by periodic applications of a dark, oily, and viscous liquid referred to in the literature as “resin” or “oil”. The oil served the dual purpose of protecting the wood from insects and of creating the proper aesthetic effect to warn unauthorized persons from opening the reliquary box. Formulation of the oil is of some mystery, but it was probably a combination of charcoal dust, copal resin, and palm oil. Some traditions replaced the charcoal dust with padauk powder to give the figures a red-brown color, especially where female byeri figures were more common.

The collection contains a good number of authentic Fang works, and the present example is perhaps the most artistically captivating. The style of the figure is consistent with that identified as “Ntumu”, especially in the way the neck continues the width of the torso and in the rounded bulges of the muscles. The level of wear to the features under the patina indicate a long history of use. The patina itself probably once oozed black, but after many years as a display object in the West has hardened and crackled, though a recent light application of palm oil has brought back much of the black luster. In its hands the figure holds either an initiate’s whistle or a horn holding the psychedelic brew containing ibogaine that is used for bwiti initiations.

The extreme sensuous curves of the figure remind us that a byeri is not to be confused for a literal representation of a human. Rather, a byeri is a human-form “seat” for ancestral spiritual power that is otherwise indescribable in human terms.

A related figure in the Barbier Mueller collection has the same hairstyle, the same design on the torso, and also holds a whistle/horn, but has had the mouth chipped away for takings of material that would have been used in medicines or ritual; presumably it originally had a beard similar to the collection’s figure. The Barbier Mueller figure either did not have an oily patina or was cleaned of it at some time in the past, and comparison to the collection’s figure shows that the Barbier Mueller figure is likely to have had a shorter history of traditional use than the collection’s figure, thus the greater cultural accumulation on the collection’s byeri.

References

http://www.randafricanart.com/Fang_byeri.html

Perrois, Louis, “Fang“, Visions of Africa Series, 2006

https://www.imodara.com/discover/gabon-fang-eyema-bieri-reliquary-guardian-figure-ntumu/