The people known as Hungaan, also called Hungana, have a modern population that is only in the hundreds. Their closest linguistic relatives are the Suku and the Yaka, and their art contains similarities to those cultures, yet is distinctive on its own.

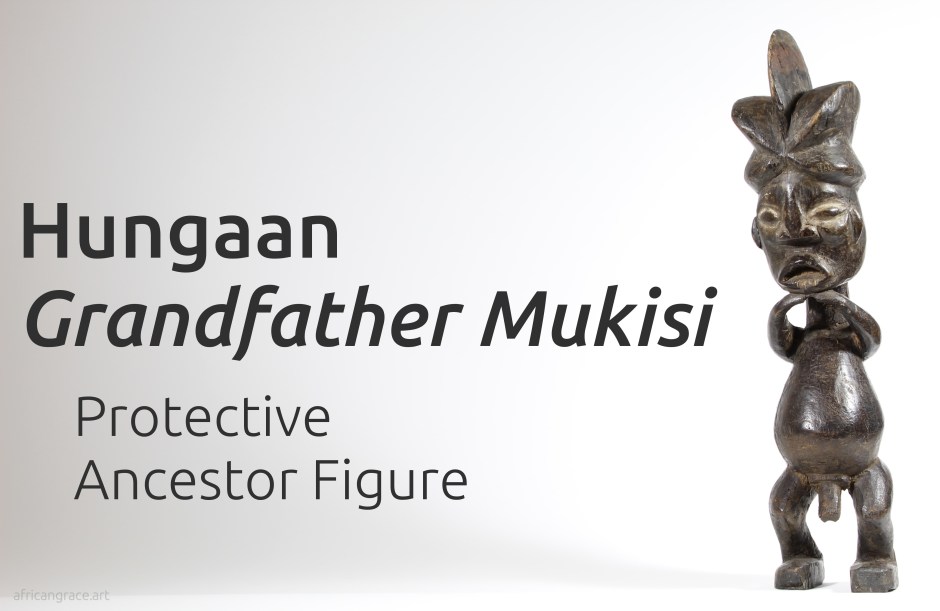

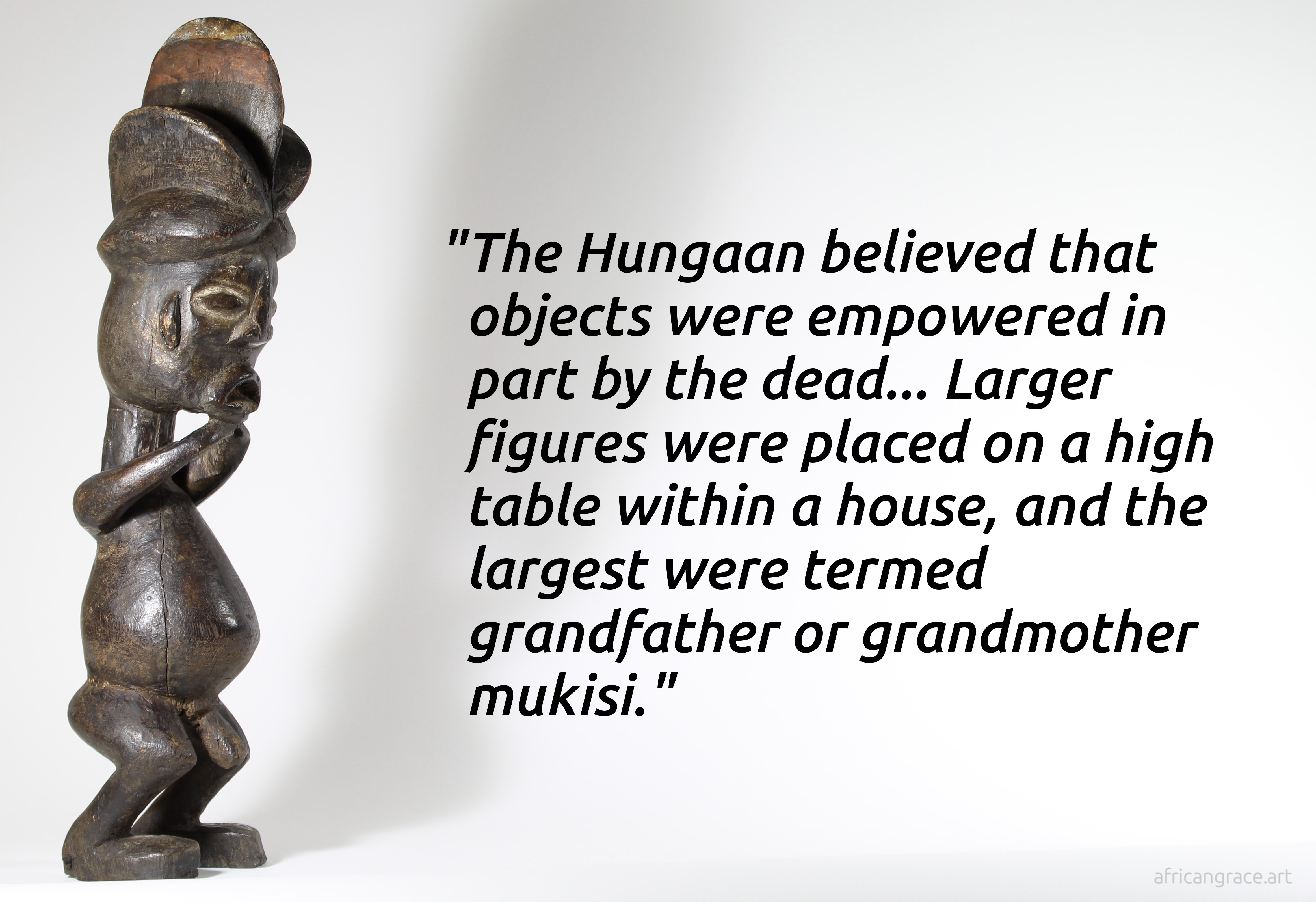

The Hungaan are best known for their old ivory works that have stood the ravages of time, unlike most of their wood objects. The most obvious aesthetic feature of their sculpted figures is the hands brought up to the chin, with the arms surrounding a void of space above a rounded belly. A large headdress is also typical.

Though Hungaan artists are best known for their ivory figures some wood figures have survived in museums and personal collections. The collection’s own Hungaan figure is carved of a very dense and tough wood, a trait that helped ensure its survival to the present day. It’s remarkable patina attests to many years of use; battered and worn and even more visually powerful as a result. Many different repairs confirm its importance to the original owner(s).

It is believed that figures such as this one were protectors of a household. They were placed in a special location or shrine, typically with smaller figures attached by cords around the waist. Called “grandfather” the figure and its group of smaller figures would provide ancestor spirits a “residence”, or a locus from which they could interact with the human world. From this place they could protect their descendants from the less benevolent forces surrounding them.

Surviving Hungaan wood figures are very rare, so rare that the limited corpus is unlikely to ever find a distinct place in the canon of classic African sculpture, and surviving examples will more likely remain ethnographic curiosities than art auction superstars. It is believed that the tradition that used the figures disappeared around the turn of the 20th century, meaning that it likely peaked well before then and most wood mukisi figures were lost to time before western collectors arrived on the scene. It is not unreasonable to suggest that the famous Hungaan ivory pendants are surviving echoes of a much larger tradition in wood that thrived and naturally faded well before colonial history was written in the area.

The best-known grandfather mukisi figure resides at the Berlin Museum für Völkerkunde and was acquired in 1886. The Berlin figure is complete with its miniature figures so we know what a full ensemble would look like.

Considerable wear on the torso of the collection’s mukisi seems to indicate it would have had similar figures tied to it.

As a work of sculpture the collection’s figure is special; in balancing geometric forms the tension it creates is palpable. From the front view the basic cylinder of the body is interrupted by the round void created by the arms, creating visual tension. The void is harmoniously echoed by the head, the belly, and the shape of the bowed legs. Clever asymmetries create visual cues of stored energy ready to burst into motion. From the profile view it looks as if the artist used two cylinders and intersected them at the neck, the top cylinder overhanging the bottom cylinder and creating a physical tension as if the figure is ready to leap forward in defense of its caretakers. The overall impression is one of both power and grace.

More examples

References

http://raai.library.yale.edu/site/index.php?globalnav=image_detail&image_id=5737

http://raai.library.yale.edu/site/index.php?globalnav=image_detail&image_id=3916

Click to access Art_and_Oracle_African_Art_and_Rituals_of_Divination.pdf

https://www.mfa.org/collections/object/figure-4763

https://www.dia.org/art/collection/object/standing-figure-48541

Alisa LaGamma, John Pemberton, Art and Oracle: African Art and Rituals of Divination, 2000